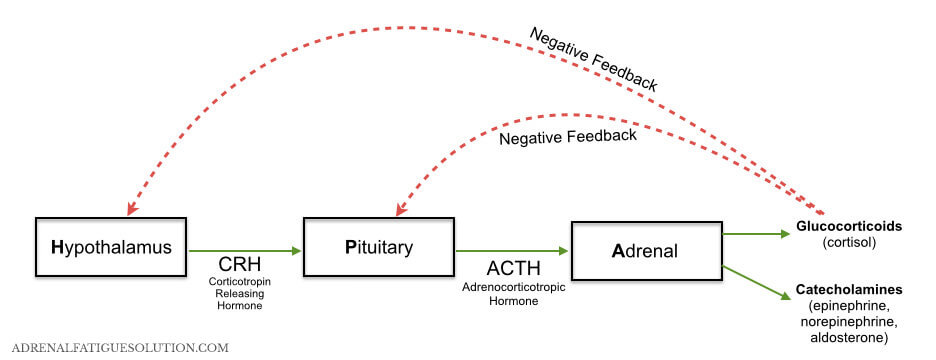

The HPA axis is a complicated set of relationships and signals that exist between the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland and the adrenals. This relationship is an absolutely indispensable part of our existence. It’s a complicated subject, and the way that the adrenals, the pituitary gland, and hypothalamus interact with each other has been the subject of considerable research.

The HPA axis is a complicated set of relationships and signals that exist between the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland and the adrenals. This relationship is an absolutely indispensable part of our existence. It’s a complicated subject, and the way that the adrenals, the pituitary gland, and hypothalamus interact with each other has been the subject of considerable research.

On this page I am going to try to give a summary of each of the elements in the HPA axis and how they interact with each other. Without this knowledge, really understanding adrenal fatigue is impossible. This simplified representation is enough for you to get an idea of what the HPA axis really does.

Introduction to the HPA Axis (University of California)

The Endocrine System – An Overview (Thyroid UK)

1. The Hypothalamus

The H in HPA stands for Hypothalamus, a small part of the brain that does a very big job. Its function is to send messages from the brain to the adrenals, the pituitary and other organs, so it is usually considered to be the starting point in the HPA axis. It is ultimately responsible for things like your circadian rhythm, your body temperature and your energy levels.

The Hypothalamus (University of Wisconsin)

2. The Pituitary Gland

The pituitary gland is even smaller than the hypothalamus, but it produces an extraordinary number of hormones that our bodies need. For example, this pea-sized gland produces vital hormones like Growth Hormone, Anti-Diuretic Hormone and Luteinizing Hormone. It is physically connected to the hypothalamus and sits at the base of the brain.

The Pituitary Gland (Patient.co.uk)

3. The Adrenal Glands

Lastly, we have the adrenal glands. We each have two of them, and they sit just above our kidneys. Although physically separate from the hypothalamus and pituitary glands, they are deeply connected. The adrenals produce even more hormones than the pituitary gland does – steroid hormones like cortisol, sex hormones like DHEA, and stress hormones like adrenaline and dopamine. The hormones produced by the adrenals control chemical reactions over large parts of our bodies, including something you might have heard of called our ‘fight-or-flight’ response.

The Adrenal Glands (University of Maryland Medical Center)

How do the different parts of the HPA axis interact?

That’s the simple explanation of where each part of this network sits and what it does, but the really interesting bit comes when you see how they interact. So let’s take a walk through a typical response to a stressful situation.

We begin with the stressor. That could be a moment of imminent physical danger, or it could be simply thinking about a public speaking engagement next week. Whichever it is, the reaction from your body is pretty much the same.

Next, your hypothalamus releases corticotrophin-releasing hormone, which sends a message to the pituitary. This stimulates the pituitary’s ACTH production, which then prompts your adrenals to make cortisol. Among other things, cortisol raises the sugar in your bloodstream and prepares your body for the high-energy ‘fight-or-flight’ response that it is anticipating. Your adrenals also release adrenaline, which raises your heart rate and increases your blood pressure.

These interactions continue until your hormones reach the levels that your body needs, and then a series of chemical reactions begins to switch them off. For example the cortisol released by the adrenals actually inhibits the hypothalamus and pituitary (so they stop sending signals to produce more cortisol!). This is just one of the automatic switches that we call negative feedback loops, and these loops are one reason why the HPA axis is so extraordinary.

So what happens when you have severe adrenal fatigue? Well, those signals might still get sent from the hypothalamus to the pituitary gland, and from the pituitary gland to the adrenal glands. But when the message reaches your adrenals, nothing happens. The adrenal glands have become so depleted that they are unable to release or produce the hormones that you need to react to a stressful situation.

In fact, our body constantly needs the hormones that the adrenal glands produce. When they become this worn out, we find that many of our hormone levels begin to drop. Other parts of the endocrine system attempt to compensate for the weakened adrenals, but that only leads to lower hormone and neurotransmitter levels elsewhere. Soon, we start to feel constantly tired and lethargic, and exhibit the typical symptoms of adrenal fatigue. For more information on how this happens, read my post on on the four stages of adrenal fatigue.